Student Mentoring

Sources of Motivation

In the mid-1990s, I attended a number of faculty development workshops intended to improve my teaching and student mentoring. Examples included the Agricultural Bioethics Forum (Bioethics Institute; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 14-19, 1995), the Campus Writing Program Faculty Workshop (University of Missouri-Columbia. January 10-12, 1996), and the Wakonse Conference on College Teaching (Miniwanca Conference Center, Shelby, Michigan. May 24-29, 1996). These (and other) workshops provided me with the tools needed to skillfully introduce bio-ethics topics in the science classroom environments, as well as to use writing to improve the students’ meta-cognitive skills. At one of these workshops, I was particularly inspired by a report from the NSF Division of Undergraduate Education on the Review of Undergraduate Education in Science, Mathematics, Engineering and Technology titled “Shaping the Future: New Expectations for Undergraduate Education in Science, Mathematics, Engineering, and Technology (NSF 96-139)”. The report strongly argued the use of research to benefit undergraduate education. This report was the result of the work of an NSF committee chaired by Dr. Melvin D. George, former interim president of the University of Missouri system. The report recommended educators to put more effort in teaching and mentoring to improve undergraduate education.

Other studies have long established that mentoring in a science research laboratory develops students into independent researchers, empowering them to take personal responsibility for their scientific decisions and less likely to drop out of the college learning experience [J. of Res. in Science Teaching, 33:799-815; Studies in Science Education, 22:85-142; J. of Research in Science Teaching, 31:197-223]. However, the role of the mentor is critical. Hodson [Studies in Science Education, 22:85-142] strongly argues that mentors should take their role more seriously in order to maximize this potential; he asserts that “the only effective way to learn to do science is by doing science, alongside a skilled and experienced practitioner who can provide on-the-job support, criticism and advice” (page 120). These studies and other observations argue for the importance of mentoring as a critical part of undergraduate education. These were sources of inspiration for me.

Student Mentoring at the University of Missouri-Columbia

I was involved in the training of postdoctoral fellows, graduate students and undergraduate students in the areas of cell culture (bacterial cell growth and maintenance) cloning and mutagenesis, protein purification and characterization, crystallization and 3-dimensional structure determination, molecular modeling, manuscript preparation for publication or grant proposals, and effective ways of giving oral presentations in science.

Between 1994 and 1998, the Biochemistry Department at the University of Missouri-Columbia averaged about 150-200 undergraduate student majors a year. There were about 30 faculty members in the department. During that period, I had 22 undergraduate advisees who were all biochemistry majors. Advising entailed meeting with individual advisees at least twice a semester to review their academic progress, discuss their future career plans and offer overall guidance regarding their classroom performance and other issues in their academic lives.

I was also involved in advising graduate students. I served on dissertation committees for 8 graduate students (6 in the Biochemistry Department and 2 in the Chemistry Department). Graduate student dissertation committees met once or twice a year with each graduate student to evaluate progress and offer guidance.

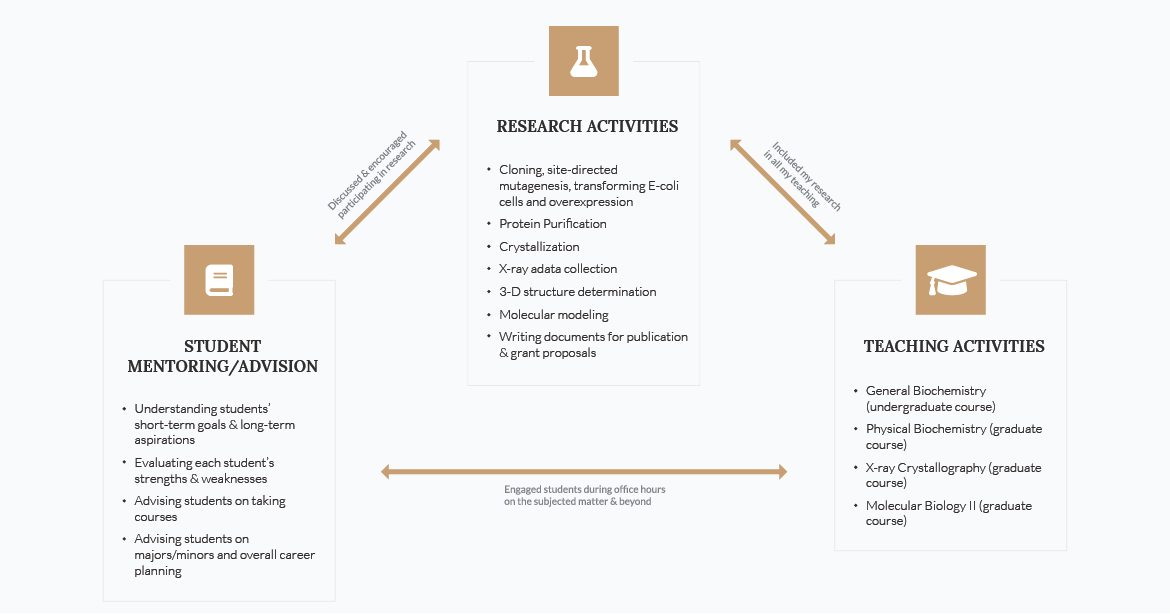

The involvement of students in my research activities was a part of an overall strategy of integrating mentoring, research and teaching. The schematic below shows how I integrated research, teaching and mentoring in my work at the University of Missouri-Columbia. Undergraduate students required more attention during the first 2-3 months of their laboratory experience. For most of them, research work in a science laboratory is a new, and sometimes intimidating. The more experienced laboratory personnel such as postdoctoral fellows, graduate students, and other senior undergraduate students spent some of their time helping to train new undergraduate students. After the first 2-3 months of learning basic laboratory procedures, the new undergraduate students were ready to embark on independent projects.

I generally met with all the students (graduate and undergraduate) individually once every two weeks. In addition, we had weekly group meetings for all members of my research laboratory. In the end, undergraduate trainees were proficient in such techniques as cloning, site-directed mutagenesis, protein purification, crystallization, molecular modeling techniques, manuscript writing, oral and poster presentations. Some became student helpers in the teaching of Biotechnology in Society (a course that I co-developed and taught) as Peer Learning Assistants (PLAs) in group discussions. This model of peer-assisted learning has been described in the literature [Groccia et al., Innovative Higher Educ., 21: 87]. Dr. James Groccia (a notable author on the topic) was the director of the Program for Excellence in Teaching at the University of Missouri-Columbia. The PLA format provides the leadership training needed for these students to build their self-confidence needed to keep them in science, and successful.

Student Mentoring at Northwest Missouri State University

Student advising and mentoring at Northwest Missouri State University took place in the context of two major programs which I headed: the Honors Program and the Missouri Academy. Students participating in both programs were academically high performing.

The Honors Program:

I worked with approximately 110 students in the newly-formed Honors Program over a three-year period (February 2005 – April 2008). I recruited these students into the Honors Program and helped them with the following:

- registration for the right sequence of Honors Program courses

- selection of majors and minors that made sense given their aspirations, personal strengths and weaknesses

- advised and encouraged them to be engaged in co-curricular and extra-curricular activities

The Missouri Academy:

The Missouri Academy was a two-year program, and thus, I had a chance to mentor individual students over that duration of time while they attended the program. I met with individual students and groups of students in formal and informal settings to discuss a variety of issues affecting their lives. Some formal settings include:

- Bridge Program: I taught a two-week course called “Effective Approaches To Studying” which was part of the Bridge Program for the Missouri Academy. I was also an adviser and mentor throughout the academic year on effective study methods and time-management.

- College Application Process: I worked with all Missouri Academy students in preparing them submit application to colleges and universities to continue their baccalaureate degree programs. I also helped students explore academic and career pathways.

- Cultural Transition Program: All new incoming international students were expected to arrive to the campus five weeks before the beginning of the Fall trimester. During this period, the new international students took the Introduction to College Writing course and participated in social events (on and off campus) intended to familiarize them with their new environment. I personally used this time to meet with individual and small groups of the new international students in an effort to help with their adjustment to a new cultural environment. I also did this to get the students comfortable with my mentoring and advising.